F1 In The 1950s: On The Edge

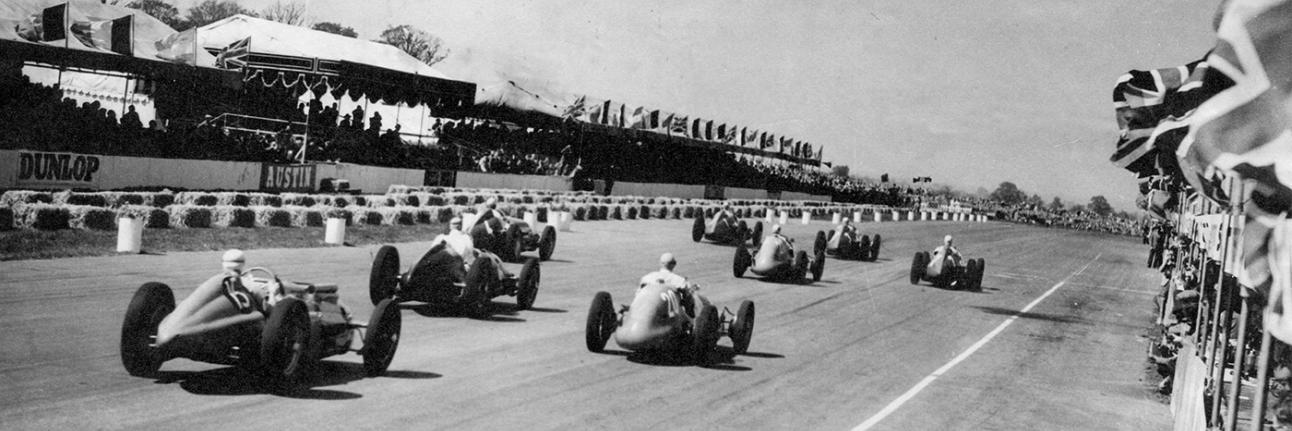

04 August 2020AHEAD OF THE EMIRATES FORMULA 1 70TH ANNIVERSARY GRAND PRIX 2020, SILVERSTONE HAS TEAMED UP WITH MOTOR SPORT MAGAZINE TO HAVE A LOOK BACK AT FORMULA 1 IN THE 1950’S

Fangio built his legacy, Alfa flourished, and a fleeting, game-changing Mercedes return led to battle with Ferrari. Doug Nye looks at how F1 came back from the brink to thrive.

Just bear with me a moment, and think back to 2010. Nineteen grand prix races to decide the Formula 1 titles, and Sebastian Vettel and Red Bull-Renault wound up as World Champions.

For anyone over 35 that will seem merely an eye-blink ago. Well, imagine yourself back into 1959, Jack Brabham and the Cooper Car Company having just won their first F1 World Championship titles, and the entire decade of the ’50s would have seemed just as brief then, as 2010-19 might feel to you now.

And what a decade of racing the ’50s was. F1 itself had withered and effectively died by the Spring of 1952. It had become so feeble, so uncompetitive, that the major European race promoters strong-armed the governing FIA into awarding their World Championship titles for unsupercharged 2-litre Formula 2 instead. The result was two seasons of grand prix racing which proved barely as competitive up front as even enfeebled F1 might have provided – but at least starting grids were full.

Racing had been revived in Europe after World War II on what was effectively a run-what-you-brung Formule Libre basis. The great pre-war German factory teams of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union had been consigned to history after the devastation of war.

Pre-war, the accepted governing body of global motor sport had been the AIACR – the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus – based in Paris where ithad been created in 1904. Following WWII, authority was invested in the descendant Federation International de l’Automobile, today the FIA. Delegates then formalised Formula A, or Formula 1, in 1948.

The last pre-war grand prix formula had sought to equalise competition between supercharged and non-supercharged cars by restricting the former to a 3-litre engine capacity – the latter to 4.5-litre. A sliding scale of minimum permitted weight was also applied, relative to specific engine size. A float of pre-war non-supercharged 4.5-litre designs was pulled out from storage and revived, and racing resumed. What confronted them was a similarly pre-war generation of surviving 1.5-litre supercharged voiturette cars, mainly from Maserati but most notably from the Alfa Romeo factory, plus an array of British ERAs and one or two optimistic post-war designs, such as Geoffrey Taylor’s British Alta. Initially, post-war racing was so pre-war in character that even hard crash helmets were not made compulsory until after Luigi Fagioli’s fatal accident at Monaco in 1952.

Premier-league F1 racing thus found its feet in still-shattered and austere Europe through 1948-49. The works Alfa Romeo Alfettas dominated the former season, but the Milan company took a sabbatical on cost grounds through 1949 – exacerbated by the deaths of two great works team drivers, Jean-Pierre Wimille and Count Carlo Felice Trossi.

In 1950, enthusiastic Alfa Romeo backers funded an Alfa Corse works team’s return to racing. With its formidable, if elderly, new driver team of ‘The Three Fs’ – Farina, Fagioli and Argentina new boy Juan Manuel Fangio – they put emergent Ferrari in its place. But with Ferrari’s chief engineer Aurelio Lampredi abandoning the supercharged 1½-litre engine option for first 3.3-litre, then ultimately full 4.5-litre unsupercharged V12 engines – the writing was on the wall for Alfa Romeo.

Through 1951, the magnificent old straight-eight supercharged Alfetta, originally designed in 1937, was reaching the limit of reliable development. In seeking maximum power output, its supercharged fuel consumption soared. Races could be won on a tortoise-and-hare basis by intelligent driving (from the veteran Louis Chiron) and by a steady, reliable, economical 4½-litre straight-six Talbot-Lago camion. While the French cars trundled reliably round, the Alfettas would sprint madly, stop to refuel and change stripped tyres, then sprint again madly. Usually, their performance advantage was so great the Talbot ‘trick’ would fail. But Lampredi’s new non-supercharged Ferrari V12s could almost match Alfa power and, once reliable, they won on muscle and stamina, against straining Alfettas which had become virtual hand grenades with the pin ever willing to fall out.

Alfa Corse’s Farina became the first F1 World Champion in 1950, and it just about staved off Ferrari late in the 1951 season so Fangio could clinch F1’s second world title.

By that time, the unsupercharged Talbot-Lago T26C was another ageing design – and so was Italy’s other vetturetta-derived contender, the 1½-litre supercharged Maserati 4CLT. Another contender was the new-fangled – and unrealistically ambitious – British BRM P15, with its two-stage supercharged V16 design. BRM and its industrial backers – directed by the British Motor Racing Research Trust – outstripped their joint development budget. The on-site management’s dilettante attitude and vulnerability towards the theatrical over common sense fatally undermined that British project. Then Alfa Corse withdrew from grand prix racing, leaving only Ferrari and BRM with supposedly up-to-date F1 cars.

European race organisers opted to run their grands prix for well-supported Formula 2 instead. The V16’s game was then up when the BRDC’s Desmond Scannell and Earl Howe told BRM’s dismayed backers that their home British Grand Prix would run to 2-litre non-supercharged F2 rules.

Non-championship F1 racing would splutter on irrelevantly through 1951-52 – but it was F2 cars which took the glory. Alberto Ascari became the first man to win back-to-back titles in his four-cylinder Ferrari 500s, winning 13 times through 1952 followed by seven more in 1953.

In England, post-war austerity and rationing through the 1940s into the early 1950s was more intense and difficult to endure than during the war years. Pre-war bred racers such as Geoffrey Taylor, George Abecassis and John Heath decided to ignore such truths and “just go racing”. Taylor built his Alta cars and engines. Abby and Heath campaigned their Altas before the latter built his own HW and HWM specials, powered by Alta engines. HWM carved a tremendous reputation as underdogs challenging a European elite, and George Abecassis hadan especially adept eye for spotting and promoting new driver talent. Lance Macklin, Stirling Moss and later Peter Collins burst upon the scene as HWM drivers.

Those arch racing pragmatists, father Charles and son John Cooper, were based barely five miles from HWM’s Walton-on-Thames workshops in Surbiton. Having founded their rapidly growing specialist racing car business upon 500cc motor-cycle engined cars, for a schoolroom racing class formalised in 1950 as International Formula 3, the Coopers watched HWM’s early enterprise as part of the European road racing circus with growing interest. Big-engined F3-based 1000cc Coopers dipped into big-time races, including the Monaco Grand Prix. And for 1952 a chassis design with water-cooled four-cylinder Alta and six-cylinder Bristol engines mounted ahead of the driver carried Cooper into F2. Mike Hawthorn excelled in his Bob Chase-owned Cooper-Bristol, caught Mr Ferrari’s eye, and joined the Maranello works team for 1953. When Hawthorn beat Fangio’s works Maserati to win the 1953 Grand Prix de l’ACF at Reims-Gueux, ‘The Farnham Flyer’ was emulating Dick Seaman’s success for Mercedes-Benz in the German GP of 1938.

Other Brits had blood in their eye. Building magnate Kenneth McAlpine had funded Rodney Clark and Mike Oliver in their Connaught programme to build first Lea-Francis-engined sports and F2 cars and, from 1954, Alta-engined new-F1 cars. Then there was millionaire bearings manufacturer Tony Vandervell, an early backer of the cooperative BRM V16 project, who wanted to see a green car beat “those bloody red cars”. Such ambition did not prevent him from supplying Mr Ferrari with the Thin-Wall bearings that made his V12 and four-cylinder engines truly reliable. Nor did it prevent Vandervell from buying an F1 Ferrari to give BRM’s men real racing experience. But when his own company’s in-house inspectors found he had been sold a cobbled-up car built from largely used parts, his resolve to produce a winning British-built grand prix car ignited. Vandervell liked and admired the Coopers. He got it to design him a single-seat chassis with a Vandervell engine installed, which was derived from a mix of Rolls-Royce and Norton.

It was intended to be a 2-litre F2 entry in 1953 but was delayed until the FIA’s first new formula took effect for 1954. The supercharged option was diminished, and non-supercharged engines of up to 2.5-litres capacity were instead encouraged. This formula would outlive the ’50s and apply until the end of 1960.

Ferrari, being relatively underfunded into 1954, hoped enlarged versions of his 2-litre Ferrari 500 four-cylinder design would remain competitive. They emerged as the Ferrari 625 and won on occasion, but could never match the new elephant in the room – Mercedes-Benz of Germany bursting back upon the scene. Worse for Ferrari self-esteem, it could not really compete with the resurgent new 250F series of six-cylinder F1 cars from Maserati, just round the corner in their shared home town of Modena.

Fangio led the Maserati team but had promised himself to Mercedes-Benz whenever its new cars might be ready. That momentous day dawned as practice began for the 1954 GP de l’ACF at Reims. Mercedes transporters disgorged three gleaming new silverW196 2.5-litre straight-eight engined Stromlinienwagen cars. The performance standards of F1 changed overnight. Fangio had won GPs for Maserati starting that season, and he won more for Mercedes to end it as World Champion, for the second time.

Despite a hiccup second time out in the 1954 British GP at Silverstone, when José Froilán González and his Ferrari 625 out-performed the W196s fair and square, and when misfortune crippled Mercedes at Barcelona ’54 and Monaco ’55, German might would prevail to the end of ’55. Fangio took his third world title in the silver cars. The Stuttgart manufacturer also dominated the FIA Sports Car World Championship, but bowed out of racing at year’s end. It had made its point – and returned post-war Germany to the motor racing domination of its Third Reich predecessor between 1934-39.

But what had become of that other pre-war power, France? After the demise of the Talbot-Lagos, the handy little Simca-Gordinis and subsequent Gordinis performed Formula 2 wonders through the early 1950s, only to run out of money and vacate the scene. As did Connaught, come 1957. But not before 1955’s Syracuse GP in which young dental student Tony Brooks had made his name by using his B-Type Connaught to demolish Maserati hopes in a home-soil turnaround.

But it was left to Old Man Vandervell and his uncompromising win-or-bust approach which meant his original-series Cooper-chassised F1 cars of 1954-55 were replaced by a startling new British Racing Green teardrop car for 1956. New technical star Colin Chapman of Lotus fame created the chassis, the body designed by aerodynamicist Frank Costin. Moss drove the new car upon its debut and won the 1956 BRDC International Trophy race at Silverstone. The cars proved too green to succeed at frontline F1 level, and Fangio won his fourth world title driving Lancia-Ferrari V8s for Maranello’s Old Man – despite personal animosity between them. Maserati then picked up Fangio’s matchless services for 1957, and his fifth world title ensued – though Moss, Brooks, Stuart Lewis-Evans and the rapidly-developing Vanwall made the Italian teams sweat. The Vanwall breakthrough was made on home soil on July 20, 1957, with Moss and Brooks sharing the race-winning Vanwall.

Change was then imminent. The FIA, under pressure from the sponsoring fuel companies, banned alcohol-laced fuelbrews for 1958-60. Also, the minimum World Championship race duration and distance was slashed from three hours to two and from 500kms (310 miles) to 300kms (186 miles).

Fuel tankage could be smaller, so cars could be smaller, lighter, more nimble. A new 1500cc F2 class had been heralded for 1957-60, preceded (in Britain) by some dress rehearsal races. Cooper Cars had taken its basic F3 rear-engined recipe and instead fitted a rear-mounted water-cooled Coventry Climax four-cylinder in its 1955 centre-seat ‘Bobtail’ sports car design. For the new F2, an open-wheeled slipper-bodied version emerged as the Cooper T41. Driven by Roy Salvadori, Jack Brabham and Tony Brooks, the cars showed great speed and agility. In 1957 Salvadori suggested a larger-engined spec could be competitive at Monaco. Privateer Rob Walker funded such a car, and Jack Brabham ran third in the 1957 race until his car’s magneto bracket broke and the engine died. He pushed it across the finish line for sixth. Cooper-Climax was up and running in F2.

At the start of the new rules in 1958, the last-minute organisation of an Argentine GP featured Moss driving the Walker team’s 1.96-litre Cooper-Climax. He outfoxed Ferrari and won! Maserati had withdrawn, funding exhausted. Ferrari stood alone for Italy. That classic season was driven by drama and tragedy. Luigi Musso, Collins and Lewis-Evans all crashed fatally in grand prix races. Moss and Brooks split wins for Vanwall, and Hawthorn emerged as the first British World Champion – driving for Ferrari – winning by one point. In effect, he could have lost that point and more, had he been disqualified from the year’s Portuguese GP for driving against race direction on the pavement after a spin. Moss pleaded for clemency on his rival’s behalf. Mike’s points stood, and doing the right thing had cost Stirling his best chance of winning the title that would elude him…

Through 1958 both rear-engined Coopers and front-engined, ultra-light (ultra-fragile) Chapman-designed Lotus F1 cars used 2.2-litre interim Climax four-cylinder engines. Maurice Trintignant won another Monaco GP in the Walker Cooper-Climax with 2017cc FPF engine, two in a row for Cooper following Moss’s Argentine success. But the little cars were out-powered for the rest of that year. Rather more significantly, the newly-inaugurated F1 constructors’ world title fell not to Ferrari, but Vanwall. Having achieved his ambition – and seared by the death of his young driver Lewis-Evans in the deciding Moroccan GP – Vandervell withdrew from grand prix racing.

The head of Coventry Climax, Leonard Lee, meanwhile authorised production of full 2 ½-litre FPF racing engines to supply Cooper, Lotus and other customers in 1959. The new rear-engined cars with serious horsepower and torque confronted the front-engined V6 Ferrari Dino 246s, the four-cylinder BRM Type 25s and the new Aston Martin DBR4/250s.

That final 1959 season opened at Monaco, and Jack Brabham won for Cooper-Climax. In the Dutch GP, Jo Bonnier won for BRM in its powerful and good-handling front-engined Type 25, whose form had shown consistent improvement through 1958. At Reims for the GP de l’ACF, Brooks blasted everyone into the cornfields in his front-engined works Ferrari Dino 246 V6. The British GP at Aintree was ‘Black Jack’s again for Cooper-Climax. The weird two-Heat German GP at AVUS Berlin fell to Brooks and Ferrari.

The 1959 Portuguese GP at Lisbon had Moss match that hat-trick performance in Rob Walker’s Cooper-Climax, and when he won the following Italian GP at Monza, Cooper-Climax had clinched the constructors’. For the second successive year, the British industry had created new dominance. And in the deciding new United States GP at Sebring, Brabham led his young works Cooper team-mate Bruce McLaren into the last lap – and ran out of fuel. Bruce became F1’s youngest-yet GP winner, and Jack pushed his silent car across the finish line for fourth to become the 1950s’ final World Champion.

And now we could look back over the decade. From small, agile, rear-engined, lightweight cars – to the lavishly hefty front-engined dinosaurs. The period ended witha pure racing chassis builder – using a proprietary engine and a modified Citroën production gearbox – taking over what had long been a toolroom-standard industry preserve. The garagistes prevailed, while cheerful practicality and lateral thinking hammered the final nails into the front-engined GP car’s coffin. What a decade of racing that was…

1950’S AS IT HAPPENED

1950 World Championship for drivers begins at Silverstone on May 13. Alfa Romeo wins every qualifying race bar the anomalous Indy 500. Farina takes drivers’ title.

1951 González scores Ferrari’s first WC victory at Silverstone. Alfa on top, but champion Fangio’s Spanish GP win remains its most recent as a works team.

1952 The championship is run for F2 cars. Ascari and Ferrari dominate.

1953 Second and final year of F2 era. Ascari is champion once more – and remains the last Italian to win the title.

1954 Fangio starts season in a Maserati 250F, then switches to GP returnee (but WC newcomer) Mercedes from France onwards and storms to second title.

1955 Moss joins Fangio at Mercedes and registers a maiden WC GP victory at Aintree, though Fangio is champion again. Mercedes pulls out of racing at the season’s end after the Le Mans disaster.

1956 Fangio switches to Ferrari – an uneasy alliance, but not sufficiently so to interrupt his run of titles.

1957 Back in a Maserati 250F, Fangio is crowned for a fifth time. Vanwall becomes the first British constructor to win a WC GP, courtesy of Moss and Brooks at Aintree.

1958 Hawthorn’s consistency makes him Britain’s first World Champion, having won just one race. Moss scores first WC GP win for a rear-engined car. Vanwall wins the newly minted championship for constructors.

1959 Jack Brabham (Cooper) becomes first driver to win title in a rear-engined car.

Article written by Motor Sport Magazine